What is unhappiness?

- 9 minsDefining most things negatively is easier than defining them positively. The same should be true for happiness.

Let’s start with unhappiness. Many traditions have explanations for happiness. Some might say it comes from Enlightenment, some might say it comes from a relationship with God, and some might say people who think they are enlightened and have a relationship with God have a notably different cluster of neurons in the temporal lobe.

Here’s what we know for certain: whether you believe in God, Enlightenment, or materialism, your experience is grounded physically in your body. If you believe in God, you believe this body was created in the image of God, per Genesis 1:27. If you believe in Enlightenment, you don’t believe in any real self, and we are a fundamentally empty, dynamic interbeing of atoms. If you’re an atheistic materialist, you believe this body is this body, end of discussion.

What’s worth noting is that we are all communicating with highly symbolic language. What the Greeks might have called pneuma and the Hindus might have called prana can be explained with Western biomedical rhetoric. (The Diagnostic Statistical Manual has virtually become its own industry, earning the American Psychiatric Association more than $100 million. It listed homosexuality as a mental disorder until 1973.) I am highlighting this to avoid presentist bias.

We’ve gotten better at solving these problems with more precise speech but, to pretend we’ve understood the human body is foolish. What Jhourney is doing with neurofeedback and dhyana exemplifies this. Rather than discarding the tools from past traditions on seeking happiness, they are recognizing that all language is symbolic and, rather than secularizing Buddhist concepts to meaninglessness, they are using technology to make it more accessible. There very well might not be any inherent “stages” of dhyana in our bodies. However, there clearly are ways to achieved altered states of consciousness to find peace, and using EEG devices is a great way of synthesizing these two different symbols of communication.

Ultimately, our unhappiness is rooted in our somatic experience. We feel tension in our body. What is unhappiness? It is not something mental, it is something physical. We feel bad. I don’t think happy people understand this because unhappy people are usually, uniquely divorced from their physical selves due to past trauma. They’ve learnt to ignore their bodies and how they feel. Do you not care if you are cold outside? Do you not heat up your leftover food? Do you forget to eat if someone doesn’t remind you?

What does it mean to say your body is unsafe?

Chronically unhappy people’s bodies are not safe, so they seek solace in work, sex, substances, sleep, risk-taking, and whatever else can distract them from their somatic experience.

What is unhappiness? Rather than diving into the neuroscience of it, first let’s use language we all know. Fear, anxiety, shame, hopelessness, desperation. These emotions all elicit different physical responses. This is not just metaphor; a study of heart rate variability in unhappy would reveal this.

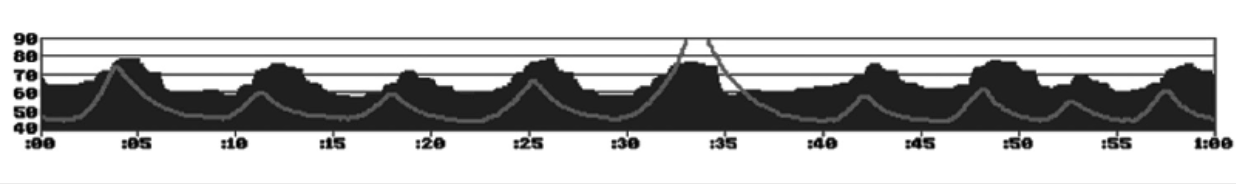

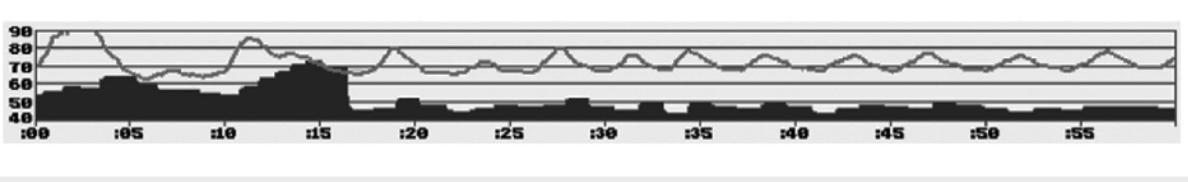

Put your hand on your chest, and find your heart beat. Notice how fast your heart is beating. Exhale. Notice how it slows down. When you inhale, your sympathetic nervous system activates. When you exhale, your parasympathetic nervous system activates and acetylcholine is released. Typically, in healthy folks, the rates of activation between these two—aka heart rate variability—should be fairly equal. Look at the graph above, and notice how the line and the shaded regions go up and down in-sync.

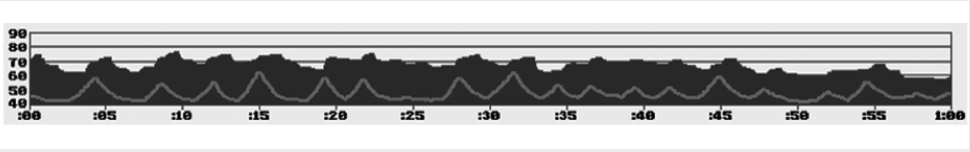

When a healthy person gets upset, notice how breathing speeds up and heart rate increases.

However, people with PTSD were found to have heart rates that were “out of sync” so-to-speak with their breathing. In other words, there nervous system did not regulate itself the way someone’s body that had never experienced trauma would. Look at this graph above. People who are traumatized literally have bodies that don’t relax as much a healthy person’s body does from breathing. The natural system is out of sync. Their bodies feel unsafe.

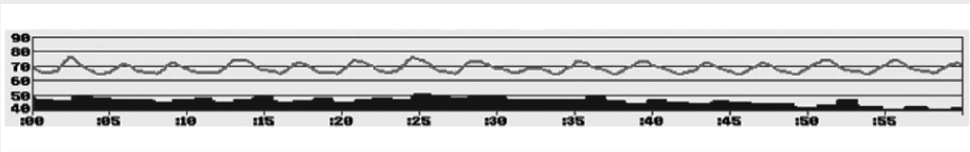

This is what a panic attack looks like. It is completely out of sync.

How many guys do you know will not wear a jacket even though it’s cold? How many girls do you know will forget to eat meals even though they’re hungry?

When Vietnam combat veterans were asked put their hands in a bucket of ice water while watching two movies, one movie a graphically violent film and the other a peaceful clip, those who watched the violent film kept their hands for 30% longer. The amount of analgesic (pain-relief) chemicals produced from watching the violent film was equivalent to 8mg of morphine. That was after watching only 15 minutes of the film. Strong emotions block pain. That’s why listening to sad music, reliving trauma, self-harm, or risk-taking are common responses that unhappy people take, despite them seeing counterintuitive. Their bodies feel unsafe, and they seek pain-relief from things that aren’t necessarily healthy in the long run. Obviously everyone’s body is different, and this is not a prescriptive take that you should stop listening to Radiohead or something—just be mindful of how our bodies work.

Can you make your body safer?

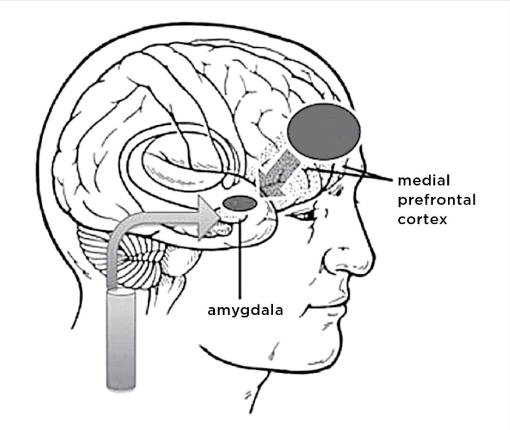

Your amygdala is the smoke detector that signals danger. Your medial prefrontal cortex is the watchtower that decides what to do by observing what happens in your mind. Fear, anger, and sadness lower MPFC activation and increase subcortical regions. Dealing with stress depends on managing top-down (MPFC-Amydala) or bottom-up (Amygdala-MPFC) regulation.

Some examples of top-down regulation are:

- practicing yoga

- mindfulness

- experiencing Nondual Awareness

- cultivating Metta

- journaling

- practicing gratitude.

These methods require more initial effort than bottom-up regulation. This is because you’re engaging your prefrontal cortex. That’s why finding the will to meditate in the morning or set aside time for journaling feels like “work.”

Here’s an example of something I do on my phone to make this easier. I keep a running list of good things that happen to me so I can control the narrative of my life: good things happen to me, I have many things to be grateful for, and I have people around me that I love, who love me.

Bottom-up regulation is how most people confront negative emotions. Common examples include binge-eating, self-harm, drug use, and social media addiction. Here’s the thing to understand though: bottom-up regulation isn’t inherently bad. What is bad, are these ways of regulating your emotions. Some healthier ways of engaging with this form of regulation include:

- Breathwork

- Pranayama

- Movement

- Qigong

- Hatha Yoga

- Touch

- Hugging someone you trust

- Adult coloring books

- Polyvagal Exercises

These are all ways to engage with the parts of your emotions that feel harder to articulate.

Nondual Awareness and Metta

I thought I’d add a section exclusively on these two concepts, though thousands of books could be written (and have been written) on them.

To experience non-dual awareness, start by asking yourself, “Who are you?” You might point to your body, but you’d still be you if you lost an arm to amputation. You might point to your brain, but then where in your brain would you exist? If you are in the brain, who is observing the brain then?

This concept is a little tricky for someone unfamiliar with this concept to understand. If you can observe something, then it can’t be you, because you are the observer. I can see my arm. Therefore I can’t see from my arm, because the process of seeing isn’t coming from my arm. Likewise, I am conscious of my thoughts and my conception of “Aadhav” or “insert-your-name-here,” therefore that feeling of “I”-ness observes the ego.

You are the underlying feeling of “I”-ness. There is nothing that says that this feeling of “I”-ness must be restricted to the skin around your body. You can expand that “I”-ness so you can identify with something greater than you. Hold on to that feeling of “I”-ness, and let everything else fall away.

That is nondual awareness.

Metta is a lot simpler to start practicing today. It simply requires cultivating compassion to yourself and to all others. Here’s a simple practice you can do today:

- Envision yourself, and tell yourself:

- May I be happy

- May I be well.

- May I be safe.

- May I be peaceful and at ease.

-

Envision the face of someone you love dearly. Your parent, your partner, your dog, your friend—someone it is easy to feel love for. Now say it towards them (“May my mother be happy. May my mother be well…“)

- Cycle through the names and faces of people in your mind’s eye. After going through your loved ones, start thinking about people you feel neutrally towards. Then work your way to people you previously felt animosity towards. Continue wishing the faces of the people in your minds eye happiness, wellness, safety, and peace.

- While you are doing this process, notice if you feel an opening in your chest or a sense of warmth. Notice how love/compassion manifests somatically in your body and pay attention to it as you cycle from people you love to people you dislike. Cultivate compassion for all of them, and direct the somatic experience of love you feel towards your loved ones to people who have wronged you.

These are both complex traditions that I can’t do justice summarizing in a blog post, so here are some resources I’d recommend checking to out hear an expert’s thoughts. For non-dual awareness, I’d recommend Be As You Are by Ramana Maharshi. For metta meditation, I’d recommend this guided meditation by Robert Burbea on YouTube.

Last thing…

This is one man’s thoughts on how to be happy. Studying and writing this is the culmination of my personal journey to be happier. I hope this can help you if you are struggling with your mental health. This is not an adequate replacement to professional help, and this is not an end-all-be-all guide. Find what works best for you.